Educational Leadership Preparation in New York State: A Landscape Analysis

Table of Contents

- Methodology

- Findings: The Landscape of Leadership Preparation

- Findings: Program Structure, Content, and Delivery

- Findings: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Preparation

- Discussion

- Implications and Recommendations

- References and Appendices

Introduction

This report provides a landscape analysis of the New York State university-based educational leadership preparation programs. This analysis is limited to programs that primarily lead to school building licensure and does not include programs leading to school district leadership or are primarily doctoral programs with a certification option.

There are many reasons for doing a landscape analysis of New York state programs, particularly given policy shifts affecting leadership preparation programs nationally. Across the United States, the field of educational leadership preparation programs has been rapidly changing, with the addition of new programs and the closing of old programs (Perrone & Tucker, 2019). There is likely a heightened sense of competition and cost differences that may be impacting content and delivery for programs to remain viable (Baum & Steele, 2018). Programs have also shifted their organization with the advent of online and hybrid formats, accelerated by the COVID pandemic.

Program content and delivery are shaped in part by state requirements for licensure (Koonce, 2009; Pavlakis & Kelley, 2016). All states have adopted standards for leadership preparation, and most have internship requirements (Scott, 2018). In 2018, the National Policy Board for Educational Administration adopted a revision of the national standards for educational leadership (the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders) and its preparation (National Educational Leadership Preparation Program Recognition Standards) (www.nbpea.org). These revised standards incorporated a stronger focus on diversity and equity, support for all students, and school improvement. Such a shift was expected to influence preparation program content and delivery.

In recent years, nationally, there has been an increased effort to diversify the leadership pipeline, beginning with the preparation and support of aspiring leaders of color (Reyes-Guerra et al., 2022). In addition, there are many challenges (Fuller & Young, 2022) and some innovative approaches (Steele et al., 2021) to leadership preparation. But it remains unclear how prevalent these challenges and innovations might be among programs, particularly in New York state.

Beginning in 2018, NYS has taken great strides to strengthen schools and districts' diversity, inclusion, and equity policies and practices through its Culturally Responsive-Sustaining Education Framework (CR-SE). The CR-SE is grounded in four principles of "1) Welcoming and Affirming Environment; 2) High Expectations and Rigorous Instruction; and 3) Inclusive Curriculum and Assessment; and 4) Ongoing Professional Learning." (https://www.nysed.gov/crs/framework). As further stated, CR-SE promotes Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) values such as diversity, inclusive learning, and work to eliminate institutional racism and cultural bias. These DEI values apply to diversity and inclusion for racial/ethnic minorities, English learners, and all students based on gender, disability, and sexual orientation. State officials provided implementation guidelines to encourage local and school districts to implement this framework, but these lacked specific guidance for leadership preparation programs.

Given these trends and policy priorities, we, as representative faculty of leadership preparation programs, were interested in learning more about how New York state leadership preparation programs address the state's DEI priorities and their approach to leadership preparation generally. We began by exploring the landscape of preparation programs and their program delivery to answer the following questions:

- What is the landscape of leadership preparation programs throughout New York State? How does program availability differ by region and public/private status?

- What is the nature of program structure, content, and delivery, and how does this differ by region?

- How do programs prepare leaders for diversity, equity, and inclusion practices, and how do these approaches differ by region?

This research is made possible through the Diversity Leadership Initiative, supported by a grant from the New York State Education Department (NYSED) to Stony Brook University. The initiative's aim has been to address the shortage of diverse and well-prepared K-12 school leaders throughout New York State. Facilitated by faculty from five universities, namely Stony Brook University, City College of New York, Fordham University, Hofstra University, and St. John's University, this initiative is a collaborative effort to promote a diverse leadership pipeline. This leadership preparation program investigation provides a foundation for exploring further initiatives.

Methodology

Conducting the landscape study required two steps—identifying all New York state-approved and functioning leadership preparation programs and collecting data about their program structure, content, and delivery, including their focus on leadership and diversity, equity, and inclusion, and number of graduates.

Identifying Programs

The first step involved identifying all the current School Building Leader (SBL) programs across New York State. Data collection for this project occurred in two parts. First, we accessed the New York State Education Department (NYSED) "Inventory of Registered Programs" page, which listed 50 state-registered school leadership programs.

Second, for each identified program, we looked up its respective university and department website from August 2023 to June 2024 to confirm its status. In this review, we determined which programs were still in operation and which had been closed. A key outcome of this inventory was confirming that there were 37 currently active programs in New York State.

To understand the geographic spread of programs, we sorted and classified the leadership programs by region, as designated by New York State (https://www.health.ny.gov/publications/0548/special_education_services). In all, there were 37 programs, as shown in Table 1 by region; see Appendix A for the list of active programs.

| Region | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Long Island | 6 | 16% |

| NYC | 11 | 30% |

| Central NY | 4 | 11% |

| Lower Hudson Valley | 3 | 8% |

| Upstate | 4 | 11% |

| Western | 9 | 24% |

| Total | 37 | 100.0 |

Collecting Program Information

We collected program information for these 37 programs in three ways: website analysis, program features survey, and IPEDS data extraction.

Website Analysis

From their websites, we gathered the following information: geographic location, presence of SBL and SBL/SDL programs, contact information, and the program's URL address. This information was compiled into a spreadsheet and converted into a statewide program directory.

Program Features Survey

Design. Two project members drafted an initial survey, which the whole project team and the NYS Chancellor reviewed and provided feedback. New York State's CR-SE framework, the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders (PSELs), and Rabb, Generett, Good & Theoharis's (2021) book Five Practices for Equity-Focused School Leadership guided the development of survey items. To test the quality of the survey, we conducted face validity with three educational leadership professors whose programs represented three different regions from across New York State. Additionally, we had key State-level educational leaders review the survey. We integrated feedback from these key stakeholders. The final survey was designed to collect the following information for each program: geographic location, presence of SBL and SBL/SDL programs, number of credits required, modality of offerings, program costs, faculty attributes, student demographics, and a commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) programming.

Fielding. The survey was fielded in Spring 2024 by emailing the program directors of the 37 active programs, with five follow-up requests. Once we hit a 75%-response rate, we turned to contacting program directors directly from the nonresponding institutions and interviewed them to complete the survey for them.

In all, we were able to achieve a 97% response rate, with one program not responding. Additionally, we removed one program because the coordinator shared that their SBL program was embedded within a doctoral program and they did not provide information on their institution's free-standing SBL program. For this study, we are only looking at dedicated school building leadership preparation programs and excluding those that were embedded in doctoral programs. Thus, we had only 35 programs with usable survey responses.

Extracting IPEDS Data

To document program outcomes, we developed a dataset on the number of graduates using the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) for the 2023–2024 academic year. We searched for the outcome measures—Postgraduate Certificate and Master's—for all 37 colleges and universities in New York State offering educational leadership programs.

IPEDS classifies program outcomes using multiple taxonomies. Of the 14 available taxonomic categories, we included only those directly related to the principalship; programs focused on the superintendency were excluded. Most institutions report principal certification graduates under "Educational Leadership and Administration, General," while a few use "Instructional and Curriculum Supervision." One institution uses "Elementary and Middle School Administration/Principalship." We combined the data for Educational Leadership and Administration, General and Instructional, and Curriculum Supervision to produce the final dataset. This dataset was uploaded to SPSS and merged with our existing survey and website data for analysis. The publicly available IPEDS data results by institution are included as Appendix B.

Analysis

We combined the website, survey data and IPEDS data into one data set. Where there were inconsistencies, we relied upon the program director survey feedback to be the most up-to-date. The data were then analyzed using SPSS to generate descriptive statistics and crosstabulations of program features and delivery by region of the state and public or private status, testing statistical differences where relevant.

We learned in our analysis that some institutions have several programs or offer the same program through different modalities. As we gathered survey data from one program director for each institution, we are assuming that the responses reflect all versions of the programs for institutions with more than one program.

Findings: The Landscape of Leadership Preparation in New York State

Our first question was intended to capture the landscape of leadership preparation programs in New York State. We counted programs by institution, as several institutions have multiple programs. Based on our analysis, we determined that, currently, there are 37 institutions with leadership preparation programs across New York state leading to School Building Leadership certification. These programs are listed in Appendix A.

Program Changes

In recent years, 26% (13 of 50 on the NYSED list) of the institutions had educational leadership programs that closed across the state. Three institutions closed: Concordia, College of New Rochelle, and College of St. Rose, and ten institutions discontinued or put their SBL certification programs on hiatus. In terms of sector affiliation, 92% of closed institutions are private. No public institutions closed. The only public program to close was at Baruch, CUNY. Most closed programs (69%) were in the New York metropolitan area.

Closed Programs in New York State

State-registered institutions no longer offering certificate programs:

- CUNY Baruch College

- Iona University

- Manhattan University

- New York Institute of Technology

- New York University

- Pace University

- Relay Graduate School of Education

- Utica University

- University of Rochester

- Yeshiva University

Closed Institutions:

- Concordia College

- College of New Rochelle

- College of St. Rose

Regional Distribution

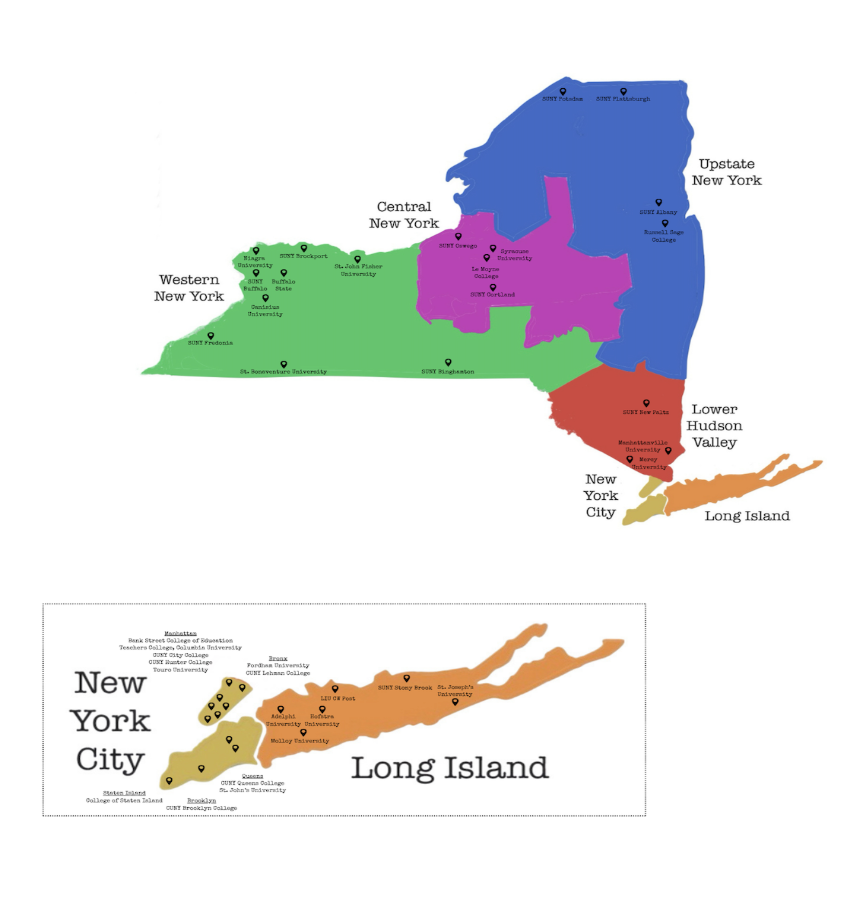

As our regional analysis shows, the programs are unevenly distributed across New York. Over half (54%) of the programs are located in the New York metropolitan area (NYC, Long Island and the lower Hudson Valley), with the most programs in New York City (30%), see Figure 1. Outside of New York City, Western New York has the most programs at 24%, followed by Long Island (16%), Central (11%), and Upstate (11%) New York. The Lower Hudson Valley (8%) has the fewest programs.

Figure 1: Dispersion of 37 Active Educational Leadership Preparation Programs by New York Region

For a complete list of institutions by region, see the New York State Educational Leadership Program Directory or Appendix A.

Institution Type

The majority of programs, 51%, are offered by private institutions. Forty-nine percent of these programs are run by public institutions, either the State University of New York (SUNY) or the City University of New York (CUNY).

The distribution of types of certificate programs varies across regions. In the Lower Hudson Valley, no institution offers an SBL-only certificate program. In Upstate New York, 75% of the institutions have SBL-only certificate programs. Conversely, all institutions in the Lower Hudson Valley prepare graduates for both SBL and SDL certification. Similarly, 75% of programs in Western New York and 70% of New York City institutions prepare graduates for both SBL and SDL certification within one program. Only 25% of institutions in Upstate New York offer SBL and SDL certification preparation within one program, making it more challenging to obtain SDL certification in Upstate New York.

| Program Characteristic | Long Island | NYC | Central NY | Lower Hudson Valley | Upstate | Western | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public or Private | |||||||

| Public | 16.7% | 60.0% | 50.0% | 33.3% | 75.0% | 50.0% | 48.6% |

| Private | 83.3 | 40.0 | 50.0 | 66.7 | 25.0 | 50.0 | 51.4 |

| SBL or SBL/SDL | |||||||

| SBL | 50.0 | 30.0 | 50.0 | 0 | 75.0 | 25.0 | 37.1 |

| SBL and SDL | 50.0 | 70.0 | 50.0 | 100.0 | 25.0 | 75.0 | 62.9 |

| Program Type | |||||||

| Masters only | — | 50.0 | — | — | — | 12.5 | 17.1 |

| Certificate only | 66.7 | 10.0 | 100.0 | — | 75.0 | 25.0 | 40.0 |

| Masters and certificate | 33.3 | 40.0 | — | 100.0 | 25.0 | 62.5 | 42.9 |

| Program Modality | |||||||

| Hybrid | 16.7 | 50.0 | 25.0 | — | 25.0 | — | 21.2 |

| Asynchronous only | — | 25.0 | — | — | 25.0 | 37.5 | 18.2 |

| Synchronous and asynchronous | 66.7 | — | 50.0 | — | 25.0 | 50.0 | 33.3 |

| Multiple modalities | 16.7 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 100.0 | 25.0 | 12.5 | 27.3 |

| Total | |||||||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

The distribution of types of educational credential options varies by region. In Central New York, 100% of the institutions' programs lead to a post-graduate certificate only. These institutions do not offer a master's degree option. Similarly, in Upstate New York (75%) and Long Island (67%), the majority of the institutions' programs lead solely to a post-graduate certificate. In contrast, 50% of the institutions' programs offered in New York City lead to a master's degree only, 10% are certificate only, and the other 40% have programs leading to both a master's degree or a post-graduate certificate. All the programs in the Lower Hudson Valley lead to both a master's degree or a certificate.

Private institutions are more likely than public institutions to offer both educational credential options (56% vs. 31%), while public institutions are more likely to offer only a credential option.

None offer only an in-person program, while 21% offer their programs as hybrid only, combining in-person and online experiences. Fifty-one percent offer their programs only online, including 18% that offer only an asynchronous program option, which means they never meet, and 33% offer synchronous and asynchronous. The remaining 27% of programs offer multiple program options with different modalities (e.g., a hybrid program and an online program).

There are some regional differences in where hybrid-only programs (with their in-person components) are offered: The majority of institutions' programs on Long Island and in Western NY are only online, while all the Lower Hudson Valley programs include hybrid options.

Public institutions are more likely than private institutions to offer the hybrid program option (60% vs. 40%).

Number of Graduates

The institutions' programs varied widely in the number of graduates earning either a post-graduate certificate or a master's degree. This ranges from a low of 0 to a high of 165 graduates in 2024, based on IPEDS reporting data. Table 3 shows the average number of program graduates by region and the total number of graduates by region in 2024.

| Region | Average number per program | Sum among programs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-grad certificate | Master's | Total graduates | Post-grad certificate | Master's | Total graduates | |

| Long Island | 60 | 7 | 67 | 359 | 42 | 401 |

| NYC | 8 | 30 | 38 | 76 | 270 | 346 |

| Central NY | 32 | 6 | 38 | 126 | 25 | 151 |

| Lower Hudson Valley | 24 | 7 | 32 | 57 | 0 | 57 |

| Upstate | 13 | 2 | 15 | 39 | 6 | 45 |

| Western | 9 | 6 | 15 | 60 | 42 | 102 |

| Total | 23 | 13 | 36 | 733 | 407 | 1140 |

The average number of graduates by institution is smallest in Upstate New York and Western New York (15 graduates) and largest on Long Island (67 graduates). The state averages 13 master's graduates and 23 postgraduate certificate graduates by program.

According to the IPEDS data, there were 1,140 educational leadership graduates statewide in 2024, 36% of whom earned a master's and 64% earned a postgraduate certificate. The total number of graduates varied widely by region, with 35% from Long Island institutions' programs. The smallest number are graduates of programs in institutions in the Lower Hudson Valley and Upstate New York. These figures represent the location of the institution of the leadership preparation program and not the graduates, however. Several institutions have programs that are online and serve aspiring leaders from around the state. Other programs have partnerships with districts in other parts of the state, as well, which may skew how graduates are counted by region.

The number of graduates was also analyzed by type of institution, as shown in Table 4. Private institutions average significantly more graduates per program than do public institutions (41 and 31 per program, respectively). Combined, 56% of all graduates earned their degree or certificate from a private institution, half of whom earned a master's degree.

| Institution Type | Average number | Sum among programs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-grad certificate | Master's | All graduates | Post-grad certificate | Master's | All graduates | |

| Public | 26 | 5 | 31 | 412 | 80 | 492 |

| Private | 20 | 20 | 41 | 321 | 327 | 648 |

| Total | 23 | 13 | 36 | 733 | 407 | 1140 |

Findings: Program Structure, Content, and Delivery

To address our second question, we identified the nature of program delivery and analyzed regional and institutional type differences. The program delivery attributes included: certificate options, program options, number of credits and instructional modality. As part of program delivery, we examined two program inputs—tuition costs and the nature of the faculty (as either full-time faculty or adjunct). Below, is the landscape of the program delivery statewide and as compared regionally and by institution type.

Certificate Options

According to our survey results, the majority of institutions offer a combined SBL/SDL program (63%). Thirty-seven percent offer only an SBL certificate program.

The distribution of types of certificate programs varies across regions. In the Lower Hudson Valley, no institution offers an SBL-only certificate program. In Upstate New York, 75% of the institutions have SBL-only certificate programs. Conversely, all institutions in the Lower Hudson Valley prepare graduates for both SBL and SDL certification. Similarly, 75% of programs in Western New York and 70% of New York City institutions prepare graduates for both SBL and SDL certification within one program. Only 25% of institutions in Upstate New York offer SBL and SDL certification preparation within one program, making it more challenging to obtain SDL certification in Upstate New York.

Private institutions are more likely than public institutions to offer the combined SBL and SDL certification program (63% vs. 56%) and are less likely to prepare graduates only for the SBL.

| Program Attributes | Public | Private | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Certification Focus | |||

| SBL | 43.8% | 37.5% | 40.6% |

| SBL and SDL | 56.3 | 62.5 | 59.4 |

| Program Type | |||

| Masters only | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| Certificate only | 56.3 | 31.3 | 43.8 |

| Master's and certificate | 31.3 | 56.3 | 43.7 |

| Modality | |||

| Hybrid | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| Asynchronous only | 13.3 | 20.0 | 16.7 |

| Synchronous and asynchronous | 26.7 | 40.0 | 33.3 |

| Multiple modalities | 40.0 | 20.0 | 30.0 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Educational Credential Option

The various institutions offer two types of graduate credential options: a master's degree, a post-graduate certificate or both options.

The distribution of types of educational credential options varies by region. In Central New York, 100% of the institutions' programs lead to a post-graduate certificate only. These institutions do not offer a master's degree option. Similarly, in Upstate New York (75%) and Long Island (67%), the majority of the institutions' programs lead solely to a post-graduate certificate. In contrast, 50% of the institutions' programs offered in New York City lead to a master's degree only, 10% are certificate only, and the other 40% have programs leading to both a master's degree or a post-graduate certificate. All the programs in the Lower Hudson Valley lead to both a master's degree or a certificate.

Private institutions are more likely than public institutions to offer both educational credential options (56% vs. 31%), while public institutions are more likely to offer only a credential option (see Table 5).

Number of Credits

The institutions' programs averaged about 31 required credits in length, but ranged widely from 22 to 36 credits (see Table 6). This average and range masks wide variations among the programs: Five programs require 22-26 credits, while 7 programs require 35-36 credits. This variability was unrelated to whether the preparation programs are only for School Building Leader (SBL) preparation or a combination of school and district leader preparation (SBL/SDL).

The average number of required credits varied somewhat by region and institution type. The range was from a low average of 29 credits for Long Island institutions' programs to almost 33 credits for Upstate New York institutions' programs (see Table 6).

There was a statistically significant difference between public and private institutions in the number of required program credits, with public institutions requiring more credits on average than private institutions (32.6 vs 29.2 credits) (see Table 7).

| Program Attribute | Long Island | NYC | Central NY | Lower Hudson Valley | Upstate | Western | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of credits | 29.17 | 31.00 | 30.75 | 31.00 | 32.75 | 30.88 | 30.83 |

| Tuition per credit | $915.75 | $764.78 | $552.50 | $840.33 | $516.91 | $700.56 | $725.21 |

| Total program cost | $26,077.50 | $23,911.89 | $16,930.50 | $26,210.00 | $17,463.73 | $20,625.96 | $22,138.48 |

| Average percentage of students who are (2024) | |||||||

| Female | 67.60 | 78.80 | 71.67 | 65.00 | 65.00 | 71.25 | 72.13 |

| White | 67.80 | 43.50 | 65.00 | 44.00 | 65.00 | 78.38 | 60.61 |

| Urban | 18.33 | 88.80 | 40.00 | 28.33 | 17.50 | 24.38 | 43.09 |

| Staffing | |||||||

| Number of full-time faculty (tenure and clinical) | 1.33 | 4.00 | 2.63 | 3.00 | 4.33 | 1.43 | 2.70 |

| Number of adjuncts | 21.17 | 10.67 | 9.00 | 5.00 | 7.75 | 5.29 | 10.36 |

| Program Attributes | Public | Private | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average number of credits* | 32.59 | 29.17 | 30.83 |

| Average percentage of students (2024) who are: | |||

| Female | 73.00 | 71.31 | 72.13 |

| White | 61.20 | 60.06 | 60.61 |

| Urban | 45.00 | 41.28 | 43.09 |

| Program Cost | |||

| Tuition per credit* | $509.13 | $991.15 | $725.21 |

| Total Program Cost (tuition x credits)* | $16,498.81 | $29,079.62 | $22,138.48 |

| Staffing | |||

| Average number of full-time faculty (tenure and clinical) | 3.14 | 2.36 | 2.70 |

| Average number of adjuncts | 10.50 | 10.24 | 10.36 |

*p<.01

Modality

The institutions delivered their School Building Leadership (SBL) programs through a variety of modalities. None offer only an in-person program, while 21% offer their programs as hybrid only, combining in-person and online experiences. Fifty-one percent offer their programs only online, including 18% that offer only an asynchronous program option, which means they never meet, and 33% offer synchronous and asynchronous. The remaining 27% of programs offer multiple program options with different modalities (e.g., a hybrid program and an online program).

There are some regional differences in where hybrid-only programs (with their in-person components) are offered: The majority of institutions' programs on Long Island and in Western NY are only online, while all the Lower Hudson Valley programs include hybrid options.

Public institutions are more likely than private institutions to offer the hybrid program option (60% vs. 40%) (see Table 5).

Program Cost

A key part of program structure and delivery is cost, which we found varied widely among the programs and regions. The average cost of tuition in 2023-24 among the reporting institutions' programs was $725 per course credit, ranging from $430 to $1868.

The per-credit tuition rate varied by region from a high average of $915 per credit on Long Island to a low average of $517 in Upstate New York. These regional differences in part reflect differences between prevalence of public and private institutions, with private institutions' average tuition per credit almost twice that of public institutions ($991 vs. $509) (see Tables 6 and 7).

The average total tuition (credits*tuition) among these programs is $22,238, and ranges widely from a low of $11,280 to a high of $56,040. There were regional differences, with the highest average total tuition found in the Lower Hudson Valley and Long Island and the lowest in Central and Upstate New York. The greatest difference was by institution type, however, with private institutions' average total tuition that is 75% significantly higher than public institutions' ($29,079 vs $16,498).

Faculty and Adjuncts

Staffing leadership preparation programs varied widely among the institutions. The institutions' leadership preparation programs have an average of 2.7 tenure/tenure track and clinical faculty, ranging from 0 to 10. Public institutions have a higher average number of faculty than do private institutions (3.14 vs 2.36 faculty). There are also strong regional differences in the average number of faculty. Institutions' programs on Long Island and in Western New York had few faculty on average (1.33-1.44), while institutions in NYC and Upstate New York averaged almost three times as many faculty members (4.0-4.3).

In contrast, the institutions average 10.4 adjunct faculty teaching in their programs, ranging from 0 to 78. There was no difference between the averages for public and private institutions on the number of adjuncts used (see Table 7). But, this average ranges widely by region, from a low average of 5 adjunct faculty in the Lower Hudson Valley programs to a high average of 21 adjunct faculty per program on Long Island (see Table 6).

Relationship Among Program Attributes

We explored several relationships among program attributes and found some patterns. We correlated the number of credits, tuition per credit, number of faculty and adjuncts, number of graduates, and percentage of students who are female or white. There was no significant relationship among these, with the exception that the number of program graduates is significantly and positively related to the number of program adjuncts and average tuition per credit.

There were discernible differences by modality, however (see Table 8). On average, asynchronous-only programs are somewhat shorter than programs with other modalities, have the lowest average tuition per credit, and have the lowest percentage of students who are female (63%). Online programs (combining synchronous and asynchronous modalities) have the highest average tuition per credit, the highest average number of adjunct faculty, the highest percentage of students who are female, and the largest average number of graduates.

| Modality | Total average graduates | Number of full time faculty | Number of adjuncts | Tuition per credit | Number of credits | % Female | % White* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid | 21.8 | 1.25 | 5.20 | $726.67 | 30.67 | 76.17 | 79.00 |

| Asynchronous only | 27.0 | 3.60 | 4.20 | $632.75 | 28.20 | 63.25 | 70.25 |

| Synchronous and asynchronous | 50.3 | 2.17 | 14.70 | $759.60 | 30.60 | 78.75 | 70.63 |

| Multiple modalities | 23.4 | 3.11 | 5.00 | $643.39 | 32.00 | 66.88 | 47.88 |

| Total | 32.7 | 2.61 | 8.24 | $701.20 | 30.63 | 72.12 | 65.50 |

*p<.05

Findings: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Preparation Practices

Of primary interest for our investigation was how programs addressed diversity and social justice in their leadership preparation programs, including whether they had a dedicated course and what content topics were covered in their programs.

Dedicated Course

As shown in Table 9, 32% of the programs have a dedicated DEI or social justice course. There was wide regional variation in this course requirement. Over half the programs in Central, Western and Upstate New York had such a requirement, while none on Long Island did. Private preparation programs were significantly more likely than public programs to have this course requirement (39% vs. 25%). Examples of names of the DEI-focused course titles include: Reading for Equity and Social Justice, Leading for Excellence: Educational Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion, and Culturally Responsive Leadership.

| Region | Dedicated DEI Course (%) | Average extent of DEI Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Long Island | 0% | 4.3 |

| NYC | 22 | 4.3 |

| Central NY | 50 | 4.5 |

| Lower Hudson Valley | 33 | 4.8 |

| Upstate | 50 | 4.0 |

| Western | 50 | 3.8 |

| Total | 32 | 4.2 |

| Public | 25% | 4.1 |

| Private | 39%* | 4.3 |

*p<.05

Note: Percentages indicate the proportion of programs within each region that have a dedicated DEI course. Curriculum indicators reflect the average number of DEI-related measures integrated into the programs.

Almost all program directors (89%) indicated that DEI was integrated either moderately or extensively across all coursework (See Table 10). In open-ended questions, some program directors shared that in their programs, DEI-focused curricula occur throughout their coursework, rather than being situated in a particular course. For example, one program director explained that DEI-related content was the focus of a special education course, but then, they also "weave [it] intentionally throughout the program and internships." Similarly, another program director hailing from across the State shared that, "We weave DEI research and anti racist leadership practices into each course. We use the text, Five Practices for Equity Focused School Leadership, over several of our beginning courses."

Instructional Content and Learning Activities

We also explored how and the extent to which the institutions' programs included content that developed leadership skills to support diversity, equity and inclusion. Using a 5-point scale (1=not at all true…5=to a great extent), program directors rated the extent to which their programs covered 11 different DEI-related content and experiences for their typical students seeking school building leadership certification. The program directors rated their programs highly in the areas of developing students' capacity to strive for equity (4.9) and developing staff's cultural competence (4.84). In fact, 91% of coordinators said that to a great extent they developed students' capacity to strive for equity. Around 83% of directors reported assessing DEI content either moderately (34%) or to a great extent (49%) (See table 10).

| DEI Content | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strive for equity | 31 | 4 | 5 | 4.90 | 0.301 |

| Develop culturally relevant, coherent systems of curriculum and instruction | 31 | 4 | 5 | 4.87 | 0.341 |

| Develop professional capacity of staff | 31 | 4 | 5 | 4.84 | 0.374 |

| Support English language learners | 31 | 2 | 5 | 3.68 | 0.945 |

| Support students with disabilities | 31 | 2 | 5 | 4.03 | 0.836 |

| Support LGBTQ+ students | 30 | 2 | 5 | 3.70 | 0.915 |

| Support indigenous students | 31 | 1 | 5 | 3.10 | 1.274 |

| Emphasize continuous improvement | 30 | 3 | 5 | 4.87 | 0.434 |

| Integrates DEI throughout | 31 | 2 | 5 | 4.42 | 0.923 |

| Assess DEI skills | 31 | 2 | 5 | 4.26 | 0.893 |

| Expose students to research by scholars of color | 30 | 1 | 5 | 3.80 | 1.095 |

The 11 experiences were averaged together as an overall rating of program depth, as shown in Table 9, and compared regionally and by institution type. The results show an average of 4.2 (between moderate and great extent) among the 11 indicators, ranging from 2.9 to 5 average of extensiveness of indicator coverage. This average ranged somewhat by region, between a low of 3.8 in Western New York (reflecting "somewhat") to a high of 4.8 in the Lower Hudson Valley. There was little difference in the average number of indicators between public and private institutions.

Some program directors also shared information about the instructional content activities that were employed in their courses to support learning about diversity, equity, and inclusion. The majority of programs incorporate an equity focus in their courses by using DEI-focused case studies (86%) while 57% reported that their programs assigned DEI-focused course texts. Some program directors (51%) reported that some courses focused on racial identity development. These readings and course foci require students to reflect on how their individual backgrounds and experiences shaped their perceptions of education and society. Program directors also rated how much their programs exposed their students to research by scholars of color (3.8)(see Table 10), with only around 30% indicating they did so to a great extent.

In open-ended questions, some program directors identified active learning activities to develop DEI-related leadership skills, including equity audits (46%), simulations (37%), community walks (29%), and DEI-focused portfolio or thesis (23%). One program director described the benefit of this active learning approach referencing, "the power of community walks and projects to engage families and stakeholders." She also shared that action research (another active learning strategy) focused on bringing marginalized and minoritized students into the sphere of success." Following this theme of active learning, another program director described, "In each course in the program, students must engage in a simulation with a trained actor, and many of the simulations are DEI focused." Finally, a few programs included intensive learning experiences. For example, one program director incorporated resources and supports offered by their larger institution, including "Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation Healing Circles available to the campus." She shared that her program also participated in "social justice teach-ins, annual events on campus, and the National Day of Racial Healing."

Inclusive Practices

Notably, when it came to developing leadership capacity to support individual groups inclusively, the program directors rated their program content much lower, see Table 10. Program directors were asked to rate the extent to which they developed students' capacity to support a variety of student groups, and their average ratings reflect a moderate focus on students with disabilities (4.0 on a 5-point scale), but less so on ELLs and LGBTQ+ students (3.6), and far less on indigenous students (3.0). Moreover, only about a quarter of the program directors thought that their programs developed leadership capacity to support ELLs and SWDs to a great extent, and around a sixth believed they developed students' leadership capacity to support LGBTQ+ and Indigenous students to a great extent. To a slightly more than a moderate extent, program directors reported that they were likely to integrate DEI throughout their program and were able to assess their students' DEI skills.

We also asked program directors to rate the extent to which they developed students' leadership capacity in related areas that would support DEI goals. Program directors had a high average rating reflecting extremely positive responses regarding their emphasis on continuous improvement (4.87) with 91% saying they use these strategies to a great extent. Similarly, 100% of respondents indicated that their programs teach aspiring leaders to develop and support rigorous, culturally relevant, and coherent systems of curriculum, instruction, and assessment with 89% replying with to a great extent. Overall, directors responded positively to general curricular and DEI goals, but less so when addressing leadership capacity to support particular student sub-groups.

Alignment with PSEL Standards and CR-SE Framework

We analyzed the scope of this content in terms of the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders (PSEL) and the NYS Framework for Culturally Responsive and Sustaining Education (CR-SE) Framework (as shown in Table 11). As this standards analysis shows, the program directors rated their programs very high in addressing areas that align with four PSEL standards and the CR-SE framework, with the exception of supporting specific student groups (which is critical for promoting a community of care and a welcoming and affirming environment).

| PSEL Standards | New York State Principles of Culturally Responsive and Sustaining Education | Survey Items | Mean Rating |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equity and cultural responsiveness (3) | Welcoming and affirming environment | Strive for equity | 4.9 |

| Equity and cultural responsiveness (3) | Inclusive curriculum and assessment | Integrate DEI throughout | 4.5 |

| Curriculum, instruction and assessment | High expectations and rigorous instruction | Develop coherent systems of curriculum and instruction | 4.9 |

| Community of care for students (5) | Welcoming and affirming environment | Support students | 3.0-4.0 |

| Professional capacity of school personnel (6) | On-going professional learning | Develop professional capacity of staff | 4.8 |

Recruitment Practices

As part of our investigation, we asked program directors to identify how they recruited students, particularly for diversity. The majority of program directors (60%) reported that they recruited diverse students by targeting local school districts. At least one institution diversifies its program's students by recruiting locally. As the program director explained, "given where [our institution] is situated, recruitment efforts are concentrated in the Bronx, and we typically attract Black, Latinx, and AAPI students, many of whom grew up in and work in the Bronx, along with a few white students."

Other recruitment strategies appeared to be more generic and not necessarily targeted at diverse students, including university recruitment events (50%) and social media outreach (48%). Some institutions had targeted strategies like recruiting students via professional organizations (30%), such as the Long Island Latino Teachers Association or the Long Island Black Educators Association, or offering targeted scholarships to students from diverse backgrounds (15%). As one program director shared, "We have a scholarship for emerging leaders of color that we give out once a year to all students of color in our program."

Diversity of the Aspiring Leader Pool

From our survey, we learned about the diversity of leadership preparation students served in 2023-24. On average, 60% of the institutions' leadership preparation students are white, 19% are African American, 14% are Hispanic, 2% are Asian-American, and 3% are other. In addition, 72% are female and 43% are from urban locations (see Table 6). These percentages were fairly comparable for public and private institutions (see Table 7).

These average percentages vary widely by region, with NYC and the Lower Hudson Valley having the lowest average percentage of students who were White, and Western New York having the highest. Almost 79% of the students in NYC programs are female, in contrast to 65-71% in the other regions. Almost all the students in NYC programs (88%) are urban, in contrast to 17-18% for institutions Upstate and on Long Island.

Relationship Analysis

We had wondered whether there were any institutional, program or student characteristics that were related to a programmatic emphasis of DEI content and instruction in the institutions' programs. We found, however, that there was no statistically significant relationship between DEI-related program attributes and student demographics or program measures of tuition rates and number of credits.